Following the murder of George Floyd in 2020, the Movement for Black Lives helped catalyze a historic national racial reckoning in almost every sector and institution in the United States. Of course, structural racism did not first harm or impact Black Americans in 2020. Police violence is a leading cause of death for young men in this country – killing about 1 in every 1,000 Black men. A report from the Washington Post found that although Black women account for 13 %of women in the U.S., they make up 20 percent of the women fatally shot by the police and 28 %of unarmed killings. However, on-the-ground organizing and extensive mainstream media coverage that year of nationwide protests led to individuals, social media, and institutions pouring new attention and resources into the movements that Black activists have been leading for generations.

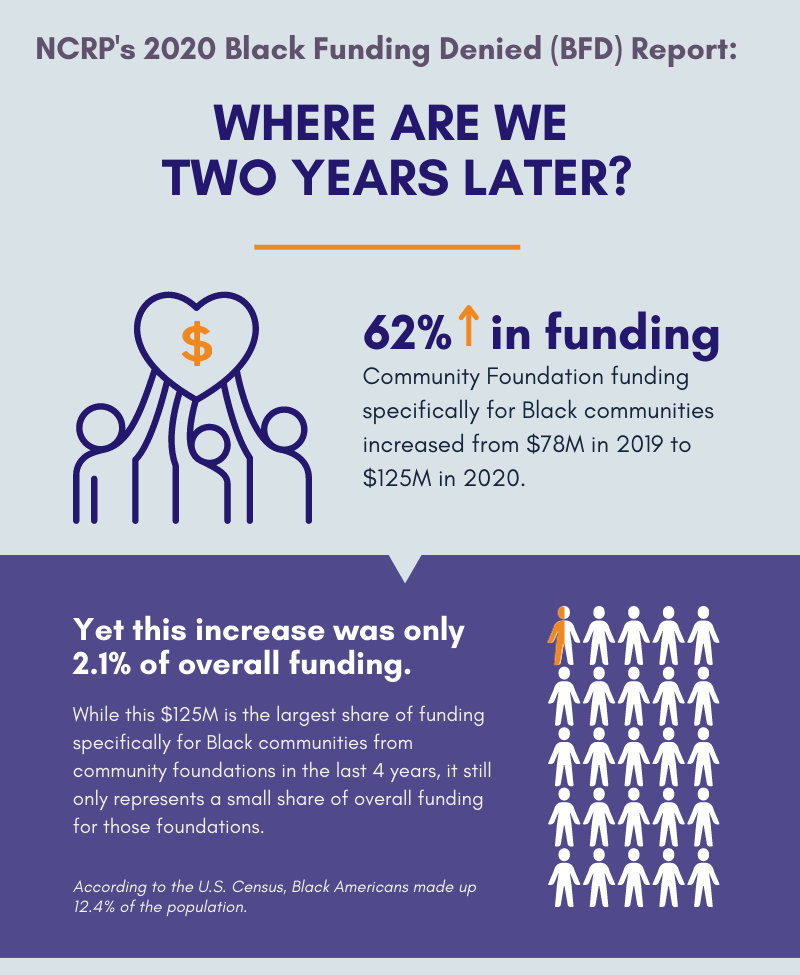

This work commanded philanthropy’s attention in new ways. We know now that in 2020, the 50 biggest public companies in America collectively committed at least $49 billion dollars. Philanthropist MacKenzie Scott alone is known to have donated at least $567 million to racial equity organizations. According to Candid’s [1] latest data, community foundations themselves granted $125 million to Black communities in 2020.

While all these financial contributions were a significant increase from previous years, this increased funding in many instances was short-term and not multi-year. The additional money in many cases has barely moved the needle for infrastructural and programmatic success for an already underfunded community that depends on foundation-based funding to survive an ever-politically unsure climate.

This is not a new conclusion and not a new ask from communities. Countless other reports have noted how if foundations are not targeting funding to specific BIPoC communities with racial equity expertise, then they are not doing enough to address the underlying conditions of structural racial injustice or inequity. As we have written often, past NCRP research and the lived experiences of a host of partners find that funders who specifically named these communities in their giving strategy were more likely to make progress against their equity goals and to hold themselves accountable.

NCRP has always sought to provide both grant makers and nonprofits with the kind of practical data and analysis that helps bridge the gap between funders’ best intentions and the reality of where their dollars go. That is why we published Black Funding Denied (BFD) at the end of the summer of 2020. Using grant and Census data, the research brief sought to report out the amount of grantmaking that some of the top community foundations were making to explicitly benefit Black people. The 25 foundations that we looked at not only represented a cross-section of some of the country’s largest community foundations, but also foundations in communities where NCRP has Black-led nonprofit allies.

More than two years later, how did our resource brief and subsequent engagement impact the conversation? What role did the community foundations we looked at play in growing philanthropic resources for Black communities?

Here’s what we found.

A Closer Look at Community Foundations Response After BFD’s Release

From Candid data as of January 19th, 2023, we know community foundations increased their annual giving for Black communities from $78 million in 2019 to $125 million in 2020. However, this $125 million was still only 2.1% of overall giving from community foundations. Comparatively, funding for Black communities specifically represented 12% of all charitable giving and 5.4% of independent foundation giving in 2020 [2].

From Candid’s initial 2020 grants data, the 25 community foundations originally studied in Black Funding Denied only contributed, in the aggregate, 2.4% of their overall grantmaking to Black communities. However, this was more than double the 1% we found these community foundations contributed to Black communities in our original research which focused on 2016-2018. In fact, in 2021, 18 of the 25 named community foundations established new grants, funds, and initiatives explicitly for funding Black communities. NCRP will work with its members and other leaders from impacted communities to keep tracking community foundation support for Black communities to observe whether any increased scrutiny on the giving of the 25 foundations named in our August 2020 research changed in the following years.

We tracked community foundations that used data on racial disparities, program officers that were motivated by Black Funding Denied, and even worked with organizations to develop new commitments in their grantmaking to Black-led leadership serving Black populations. While it’s too soon to tell the full impact of any new funding, we do know that one-time initiatives responding to the 2020 uprisings won’t be enough. A Center for Effective Philanthropy (CEP) report from 2022 showed that only 27% of foundations CEP studied are now providing more multi-year unrestricted support compared to pre-pandemic giving levels, despite pledges in the pandemic to create a new normal.

COMMUNITY FOUNDATIONS SHOULD BE LEADERS

NCRP still believes in the values we encouraged the sector to embrace in our landmark 2009 publication, Criteria for Philanthropy at its Best: the most effective grantmaking comes when funders give intentionally and deeply to build power in marginalized communities. Past NCRP research shows that foundations that invest in building power in marginalized communities see tremendous structural progress toward equity goals.

The importance of this intentionality for impactful grantmaking was also a theme in Philanthropic Initiative for Racial Equity’s Mismatched report. “Predominantly white organizations are often happy to use movement language to walk through foundation doors opened by Black, Brown, and Indigenous activists,”: wrote authors Malkia Devich Cyril, Lyle Matthew Kan, Ben Francisco Maulbeck, and Lori Villarosa. “…this kind of funding can cast leaders and organizations of color in the role of contractors helping white organizations fulfill grant requirements, rather than as grantees receiving resources for their own strategies.” NCRP has heard this anecdotally from our Black-led nonprofit member organizations and partners.

After we released Black Funding Denied, we were told by many community foundations that we should only examine their discretionary giving, rather than a larger set of assets that included their donor advised giving. We understand that it’s more than just optics. Donors can play a decisive role in where their dollars flow, even when foundations have legal control over grantmaking. We also recognize that donor education is deep, often slow work that can take time to reflect in funding decisions.

Yet to limit a community foundation’s responsibility to their community to a tiny fraction of the dollars that pass through their doors is short-sighted, and a missed opportunity.

We continue to stand with our local and national partners in believing that community foundation leaders have an obligation to proactively break down barriers between donors and underinvested communities and set racial justice as the cornerstone of their vision. This dedication to serving their full community is what should set community foundations apart.

Some funders, like Brooklyn Community Foundation, are beginning to do just that. Months after the release of BFD, the community foundation announced a historic commitment to give “at least 30 percent of all grants to “explicitly benefit Black communities,” with priority given to Black-led groups focused on systemic change. The commitment was unprecedented among community foundations because it was a long-term, rather than a temporary, grant announcement. It promised to set giving rates that matched community demographics as a floor, not a ceiling. The pledge also covered both discretionary AND donor-advised funds, recognizing the responsibility community foundations have in setting values for their donor community.

Perhaps most importantly, it included transparency, with an invitation for the community to hold the foundation accountable to this vision.

THE BIGGER LESSON GOING FORWARD

As NCRP’s Movement Research Manager Stephanie Peng has written, “data can be an important tool to get us the better world we are all striving to make by having it as an active tool that movements can use to hold foundations accountable to their commitments to equity and justice.” The value in organizing data around us is that it helps clarify how investing in the communities most impacted by structural barriers provides them – and all of us – the resources and power to succeed and thrive. While philanthropy is not always comfortable when data highlights underfunding for communities, we’ve seen that pointing out vast disparities trigger funders into action.

Transparency is key to philanthropy being able to be honest with itself and communities about the true impact of their grantmaking. Many community foundations were unaware of how their publicly available data reflected – or didn’t reflect – the numerical representation of their mission and values. While some foundations may not have the immediate infrastructure needed to support such data analysis, the resources on how to make grant data a priority is out there.

While we saw positive outcomes from individual funders willing to devote new attention to the way they share data about their giving following BFD, we also hope to see this same type of self-reflection and improvement from the field at large on how we as a sector tend to unfairly measure the success of new funds. Black communities have and will organize for systematic structural change far beyond 2020, and their leadership deserves the sector’s trust and patience through a long-term commitment of resources.

WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE

Based on feedback from NCRP’s Black-led members, our experience in dialogue with community foundations about their giving to Black communities, and findings from previous NCRP research, here are the areas where NCRP sees the most opportunity for progress:

-

- Deeper Relationship Building – First and foremost, establishing relationships and trust with Black leaders in funders’ communities will help funders center the needs of those impacted the most by past and current racist systems of discrimination and exploitation. These relationships will help funders develop strategies on how to effectively support some of the most complex problems existing within their communities.

-

- Sustained Financial Commitment – Preliminary 2020 Candid data showed that funding specifically to Black communities from community foundations from 78 million in 2019 to 125 million in 2020. While this is an exciting start, it will quickly be a thing of the past if foundations do not address how they were practicing grantmaking before 2020. Foundations should consider their internal practices, grantmaking metrics, and overall racial equity goals to ensure there is a constant flow of resources to intended communities. Funders have broken trust with communities through one-time “fad funding” before; now is not the time to repeat that mistake.

-

- Shifting Power – Community foundation leaders are not solely responsible for all of their foundation’s grantmaking, but they do have the power to influence all of it. Leaders should consider how they are wielding that power in their communities and being an active voice advocating for and with Black community members.

-

- Data Transparency – Ensure the sector has the most accurate and reliable data, by reporting timely information to Candid. Foundations who report that their grantmaking data are modeling transparency and how to hold themselves, and the sector at large, accountable.

Remember that targeting resources for Black communities specifically is not the same thing as funding racial justice work, which addresses the root causes of racial inequity. And increased funding to Black communities alone won’t be enough to repair past harm done to Black communities. Funding healing requires a separate, specific, and targeted response beyond investing in Black communities, but targeting philanthropic resources there is a great place to start.

ENDNOTES

1 Foundation Maps | Candid. (November 3, 2022). Foundation Maps.

https://maps.foundationcenter.org/home.php

2 Ibid

Katherine Ponce is NCRP’s Senior Research Associate for Special Projects. Special thanks to NCRP’s Ryan Schlegel, Stephanie Peng, and Spencer Ozer for their work on the original research that formed the basis of 2020’s Black Funding Denied.”